Chautauqua’s Living History

Every month, get an in-depth look at Chautauqua’s history from Chautauqua archivist Kate Gerard.

From Apple Orchard to National Treasure –

The Colorado Chautauqua Story

This month, learn more about Chautauqua’s previous life as the Bachelder Ranch and its earliest surviving structure, Cottage #200.

THE CHAUTAUQUA MOVEMENT

A GATHERING THAT IS TYPICALLY AMERICAN IN THAT IT IS TYPICAL OF AMERICA AT ITS BEST.

-Teddy Roosevelt

“Chautauqua” is a Haudenosaunee word with multiple meanings, including “a bag tied in the middle” or “two moccasins tied together.” The word describes the shape of Chautauqua Lake, located in southwest New York, which was the setting for the Chautauqua Institution, the first educational assembly in what became a significant movement at the turn of the 20th Century.

In 1874, John Heyl Vincent and Lewis Miller rented a Methodist camp meeting site to use as a summer school for Sunday school teachers. The camp became known as the Chautauqua Institution and reflected a nation-wide interest in the professionalization of teaching. Vincent and Miller were very clear that their intent was educational, rather than revivalist, and the Chautauqua Institution was never affiliated with any one religious denomination although the sort of mild Protestantism that informed much of American culture also underpinned the Chautauqua Movement. Today, nearly every faith group in the U.S. has a chapel or building on the grounds of the New York Chautauqua.

Within a few years, the scope of the Chautauqua Institution had broadened to include adult education of all kinds, as well as a correspondence course known as the Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle, which was designed to bring “a college outlook” to working and middle-class people. In addition to educational offerings, broadly defined to include the arts and public affairs, thousands of summer residents attended concerts and social activities. By the last decade of the nineteenth century, the Chautauqua Institution was nationally known as a center for rather earnest, but high-minded, activities that aimed at intellectual and moral self-improvement and civic involvement.

After visiting the Chautauqua Institution, Teddy Roosevelt noted it was “a source of positive strength and refreshment of mind and body to come to meet a typical American gathering like this – a gathering that is typically American in that it is typical of America at its best.”

The Chautauqua Movement grew out of the Chautauqua Literary and Scientific Circle. As its members and graduates spread the ‘chautauqua’ idea, many towns, especially in rural areas where opportunities for secondary education were limited, established “chautauquas.” Chautauquas had a degree of cachet and became shorthand for an organized gathering intended to introduce people to the new, great ideas and issues of public concern. “Independent assemblies,” those with permanent buildings and staff could be found throughout the U.S. by 1900, but were mainly concentrated in the Midwest.

After 1900, the “circuit chautauqua” became the principle expression of the movement. At the height of the Chautauqua Movement, around 1915, some 12,000 communities had hosted a chautauqua. Many of the lecturers and performers were contracted by chautauqua agencies, the most notable of which was the Redpath Agency in Iowa. The quality of the offerings varied from Vassar-educated lecturers and Shakespeare to animal acts and vaudeville farce.

The Chautauqua movement nearly died in the mid-1930s. Most historians cite the rise of car culture, radio, and movies as the causes, but there were several other important yet subtle reasons for the decline. One reason was the sharp increase in fundamentalism and evangelical Christianity in the 1920s; the bland, non-denominationalism exhibited at most chautauquas couldn’t accommodate these impulses. Many small independent chautauquas, however, became essentially camp meetings or church camps. Another seemingly contradictory influence was the rise of the liberated, educated woman. Chautauquas functioned for many lower- and middle-class women much as elite women’s colleges did for upper-class women. They were training grounds from which women could launch “real” careers. When professional and educational opportunities increased, women’s interest in chautauquas dwindled. Finally, the Depression itself made chautauquas economically impossible for organizers and audiences.

Today, chautauquas are experiencing a small renaissance. People are discovering that lifelong learning is one of the keys to living a happy, fulfilling life. Throughout North America, existing chautauquas are thriving and ones from the past are being resurrected. Learn more about all the living chautauqua communities and assemblies currently in operation at www.chautauquatrail.com.

THE COLORADO CHAUTAUQUA

A PARTNERSHIP BETWEEN THE CITY OF BOULDER, THE GULF & SOUTHERN RAILWAY AND THE TEXAS BOARD OF REGENTS

Because the Chautauqua Movement was such a powerful and popular cultural force in the United States at the time, Boulder City leaders, the Gulf & Southern Railway and the Texas Regents partnered to package a teacher’s school with a chautauqua in Boulder.

The Gulf & Southern Railway was eager to expand as far north into Colorado as possible and Boulder city leaders wooed the Texans by offering to supply land, facilities and public utilities for the assembly. They clinched the deal by promoting a ride on the narrow gauge railroad through spectacular mountain scenery to a site expressly chosen for its health-giving environment. At the time, Boulder Daily Camera Editor Lucius Paddock wrote, “The prize is too big to be allowed to slip away.”

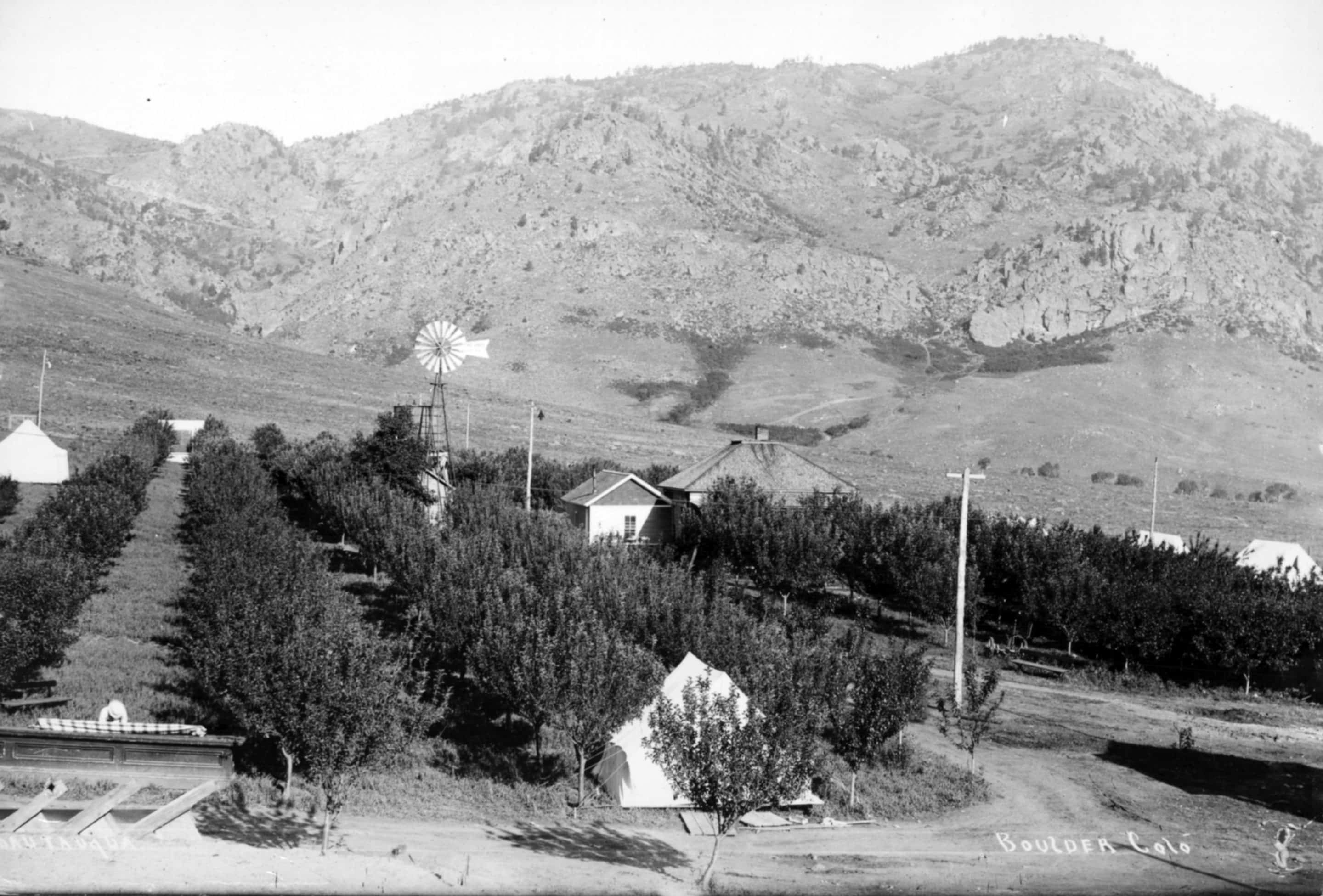

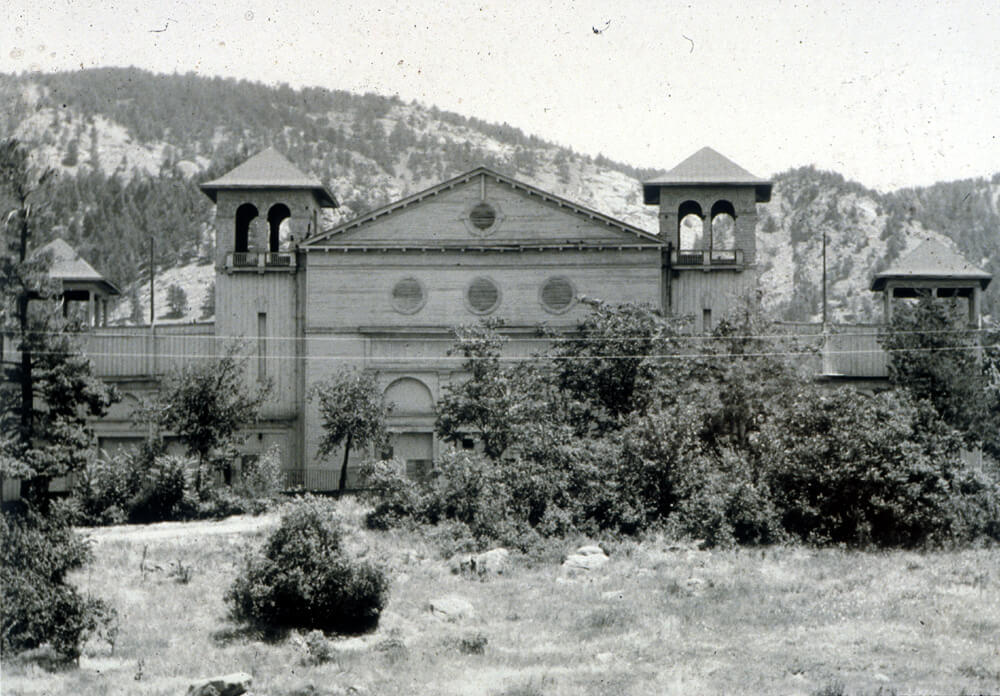

The City of Boulder purchased the 75-acre Batchelder Ranch with money raised in a bond issue, with citizens voting “yes” by a ratio of 35 to 1. The April 5, 1898 election left the Colorado Chautauqua with eleven weeks to build a dining hall, an auditorium, and a water system before Opening Day, July 4, 1898. And they did it! The City of Boulder still owns the land and leases it to to the Colorado Chautauqua Association, the organization responsible for its preservation and sustainability.

The cottages at Chautauqua, many built by John Blanchard in the Craftsman style, were constructed beginning in 1899 to replace the unsatisfactory tents of the first season. Originally used only by summer residents, the cottages are now winterized for year round use and comfort. The last one was built in 1954. The Craftsman style Missions House was built in 1911 to house students bound for the mission field and Columbine Lodge was built in 1919 for short-term visitors.